Blue Mounds History

Blue Mounds is a small town sitting upon the second highest point in Southern Wisconsin, the East Mound. It overlooks a valley that spans all the way to Illinois and stands as a beacon visible at distances over fifty miles, and it owes its legacy to the same man as Cave of the Mounds: Ebenezer Brigham.

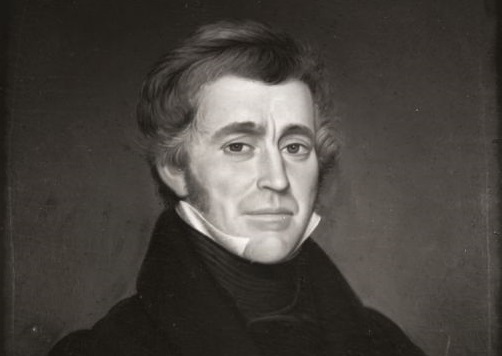

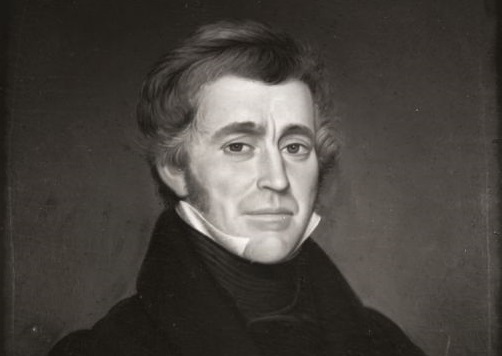

Ebenezer Brigham was a homesteader who was born in Shrewsbury, Massachusetts on April 28, 1789, to David and Martha and was raised alongside his twelve siblings. Early on, Ebenezer had decided to become an entrepreneur and pursue the age-old business of wealth. In the late spring of 1818, Ebenezer reached St. Louis and continued North to Galena, Illinois–a reputable mining town with several prospects. His journey was rather unconventional in that it began with a raft and proceeded with a canoe, a houseboat, and 200 miles walked on foot and ended with a two-and-a-half-week horseback ride followed by an ox team pulling him across the state line into Wisconsin nine years after his initial arrival in Illinois.

Ebenezer spent the majority of those nine years in Illinois building himself a mercantile business in the town of Galena which afforded him a tidy sum upon its sale: $4,000, which equates to approximately $125,500 in modern currency. He took his fortune North and landed on the East Mound in 1828 in order to dip his ladle into the stream of riches known as the Wisconsin lead rush.

Unfortunately, for the first several months of prospecting that ladle came up dry–as did his funds. With no money left to his name, Mr. Brigham was ready to call it quits. That is until a friend came to his aid. This friend provided a fresh set of funds that allowed Ebenezer to continue his pursuit and eventually strike lead.

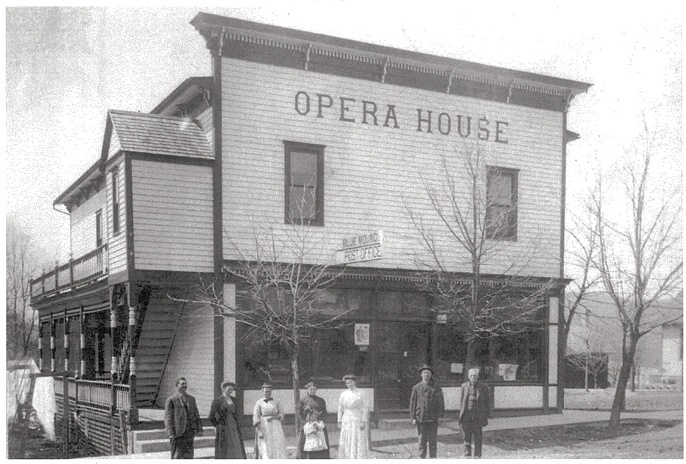

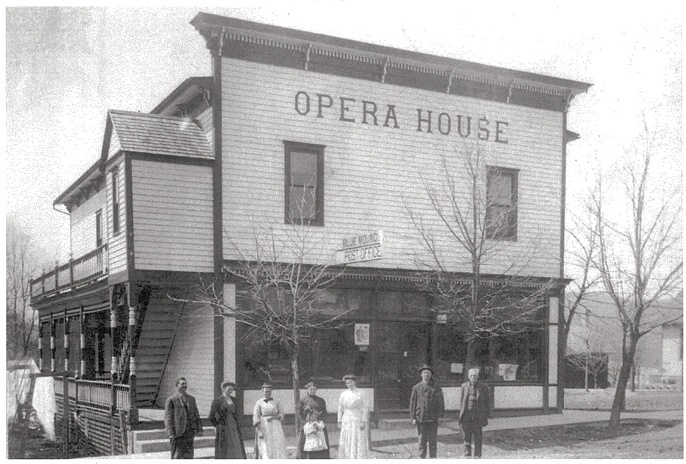

Upon his groundbreaking (literally) discovery, Ebenezer settled himself next to his mine and built a public house known simply as “Brigham’s Place,” thus founding Blue Mounds and securing himself the title of Dane County’s first white settler. As it grew in popularity, he expanded and built an inn for his workers that quickly became a rest stop for travelers heading Westward on the Old Military Road. Ebenezer’s home became an important waypoint for travelers, homesteaders, and natives alike; it was a trading post, stagecoach stop, the area’s first postal office, and the only food supplier for over 50 miles.

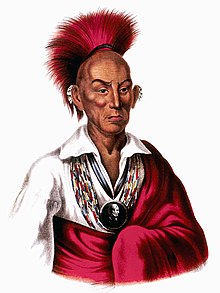

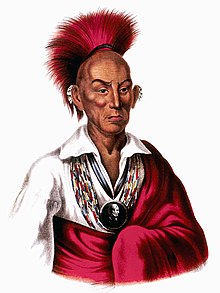

While Blue Mounds continued to grow and flourish, unrest between the native nations and the United States government began to ignite in the background. In the Spring of 1832, a metaphorical smoke rolled out along the settlements in the lead-mining district carrying the news: Black Hawk, a warrior chief of the Sauk Nation, was leading a large group of men, women, and children across the Mississippi River to reclaim the land that was ceded to the United States government due to a controversial treaty from 1804, nearly 30 years earlier. Black Hawk and his group, amounting to a little more than 1,000 Sauk, Fox, and Kickapoo, crossed the Mississippi into Illinois near the Rock River. Within a few weeks of their arrival, various militias, rival native bands, and U.S. Army troops began pursuing them in an effort to force them back West of the Mississippi River.

The group dubbed the “British Band” for Black Hawk’s continued communication with the British, made their way toward the village of the Winnebago Prophet, also known as White Cloud after the prophet sent them an invitation to the sanctuary. Black Hawk, having been effectively disowned by the rest of the Sauk for returning to their ceded homelands, continued forward under the impression that his band would receive support from both the British and local Ho-Chunk Nation. Unfortunately for his small group, he had been severely misled.

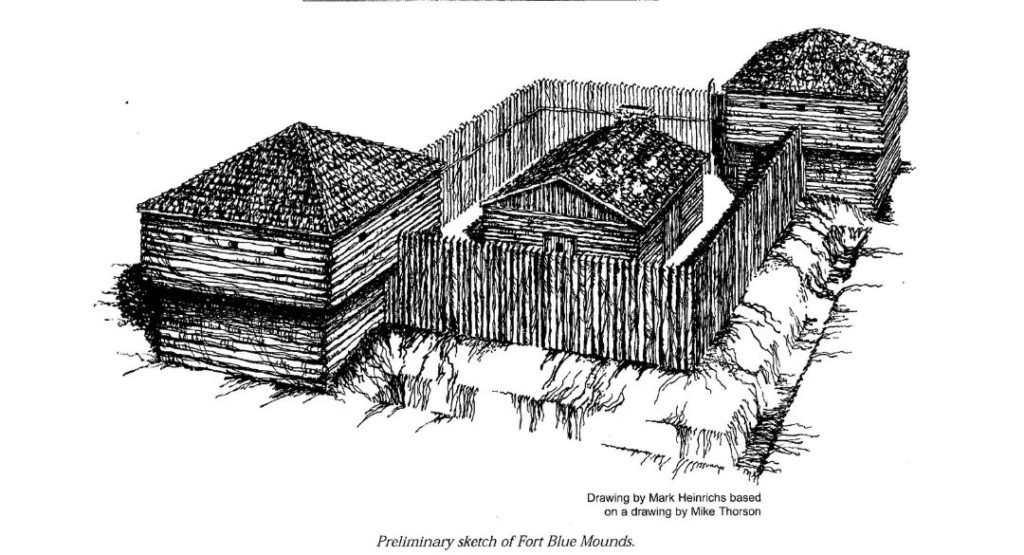

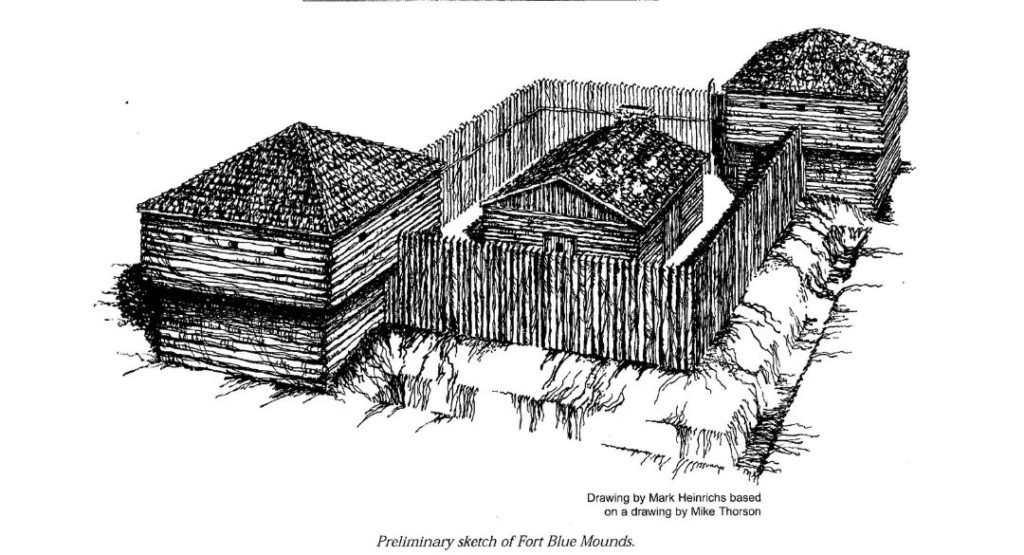

For several months, Black Hawk’s band wound their way along rivers and up into Wisconsin, eventually turning back West through present-day Madison and North across the Wisconsin River. Settlers throughout Southwest Wisconsin, then known as “Michigan Territory,” were overcome with panic and quickly erected fortifications in several areas, including Blue Mounds. Fort Blue Mounds, as it was so-called, was under the charge of John Sherman, the Captain of the Iowa Militia Company stationed at the fort. Surprisingly, Fort Blue Mounds saw very little of Black Hawk’s band and managed to escape the war with few engagements despite how close it sat to Black Hawk’s trail; however, its proximity to Black Hawk’s movements meant that it was an important fort for the purpose of supplying and reorganizing troops as they traveled.

As a man of great importance to the area, Ebenezer Brigham was given the rank of Colonel as he served in the volunteer militia as a commissary, and he lived among the troops and families that sought refuge within the fort. Brigham’s journals from this time provide a brief summary of the weekly goings-on of the war, but Brigham himself was never involved in any engagements beyond a pistol and rifle of his being stolen from one of their scouts during an ambush.

After nearly four months of the chase, punctuated by small battles and raids, Black Hawk’s War ended at the Bad Axe Massacre on the Mississippi River. After eight straight hours of attacks, the British Band was defeated. Those who survived were taken prisoner by the U.S. Army, but Black Hawk was nowhere to be seen. He had turned North the day before and was in hiding along with the prophet White Cloud among the Ojibwe. Nearly a month after the massacre at Bad Axe, Black Hawk, along with White Cloud and his few remaining followers, surrendered to a nearby Ho-Chunk village and were subsequently taken to Fort Crawford at Prairie du Chien.

After the war, life returned to something resembling normal for the settlement at Blue Mounds. Some of those residing at the fort returned to their homes, while others remained for a short period as their homes were rebuilt, having been damaged by raids during the war. The structure of Fort Blue Mounds no longer exists; it was dismantled in the late 1800s so that its wood and materials could be repurposed for the lead mines. In 1910, the descendants of the first Blue Mounds settlers deeded the land upon which the fort once stood to the Wisconsin Historical Society in order to conserve it. In 1921, a historical marker was placed at the approximate center of where the fort once stood, and in 1991, a group of archaeological volunteers convened on the property in order to map out exactly where the fort was located and to extract artifacts that could provide more information on this era in Blue Mounds’ history. Among the items collected were ornate plate ware, over one hundred lead bullets (known as shot), and a gentleman’s stamp bearing the initial “J”.

Blue Mounds was officially established as a town one month before the state of Wisconsin was in 1848. Ebenezer Brigham stayed in Blue Mounds and became involved in politics periodically, at one point serving on the Wisconsin State Assembly, all the way up until his death in 1861. After Brigham’s death, his land went to his nephew, and it is still owned by their family today, although most of it has been donated to the state and county governments for the purpose of recreation and preservation.

In the mid-nineteenth century, German and Norwegian immigrants came to Southwest Wisconsin in droves; the lush rolling hills and deep valleys reminded them of their home countries, and they settled in both Blue Mounds and Mount Horeb, a town a few miles up the road. In the beginning, they maintained separate communities with their own churches and schools and creameries, but in the 1950s, they began to consolidate themselves. Children in Blue Mounds would now attend Mount Horeb’s school district, and farmers would transport their dairy to Mount Horeb as well.

While Blue Mounds has never been a large town, it is rich in history and nature. Blue Mound State Park, which sits atop the West Mound, is only a few minutes away and boasts 1,153 acres, nearly all of which were once owned by Ebenezer. Brigham County Park also sits nearby, and, while Cave of the Mounds was not discovered until well after Mr. Brigham’s time, we still acknowledge that he remains a key factor in the discovery of this natural wonder.